Hoodie zippers catching on t-shirt fabric. Bike spokes whirring, the pump of legs up a hill. Sticky, cracking covers of thirty-pound textbooks. Grayed sneakers that slip on without untying them. A bite on the morning breeze as you shuffle to school.

Are you back there?

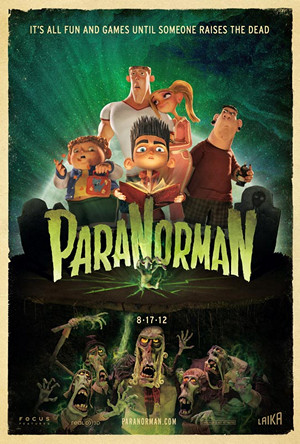

Tonight, I’m writing up one of my warm and fuzzy horrors, ParaNorman [2012, directed by Chris Butler and Sam Fell]. Yes, this is a kid’s movie and it is also horror. I wish that more stories like this would be told because children understand and process horror better than most adults. If I succeeded in stirring up some childhood ghosts in my opening paragraph, hold tight to them as we progress through this deconstruction. And click play below, if you like, for some easy listening.

This movie is a trickster. It’s disguised as a PG stop-animated feature, but it’s really very complex and very dark. Upon re-watching with pen in hand, I had moments of “oh my God,” that had never really struck me before. It takes a cue from early 1980’s kids films, using heavy thematic material like actual dead bodies, horny teenagers, bullying, lynching, and child murder. Maybe it’s the times we’re living in skewing my perspective, but some scathing critiques and really horrifying psychology are at work here. And we’re going to dig deep into this. And it’s ok, because Norman will suffer, but he’ll be ok. That’s the pact we have with children’s movies.

Love is about the details

We can’t talk about a stop-animation story and not talk about the visuals. Holy dancing cats, is this a gorgeous set. Please buy the dvd and watch the featurettes to see how much labor goes into every frame. One of the directors calls the town of Blithe Hollow a cross between Concord, NH and Salem. It’s a crappy, busted New England tourist town full of sagging houses. Pay attention to the shapes and you’ll realize that there are no straight lines. Even staircase railings are crooked. It is obsessive to the point of being unreasonable just how detailed this town is. Garbage, spray paint marking the sidewalk, leaves trapped in the edges of flat rooftops.

I geek out hard over the details of this film. The sky overhead floors me in every scene: it’s got the brush-strokes of hand-painted work, and its hues change to alter the mood of a scene. Green ectoplasm rolls off the shoulders of the zombies like cobwebs or fog. A web page for City Hall has that low-budget Geo-site-y look to it, just like in our reality.

I think Blithe Hollow was designed this way because it matches our grotesque characters. As outrageous as the shapes of the characters are, or as the director calls them, “sort of brutally honest,” this town is very real. Blithe Hollow is a fictional town that shares our actual history. America is built on the suffering of others, the unfortunate, and those who were not born with the same chances. And that same history and building material constructed Blithe Hollow and its residents.

Very possible people with impossible proportions

Norman

This is partly a character-driven story, so let’s talk people. Norman is a very smartly designed protagonist. Put aside the fact that he talks to dead people, and he still has nothing going for him in the popularity department. He’s tiny and into weird stuff. He’s sort of the runt of his school and his home life. So he just embraces who he is without letting others in, keeping his head down until the school day is finished. He keeps cleaner spray in his locker for the bullying graffiti he knows will greet him every day.

I spent a lot of time thinking about Norman’s fear. This is a movie about fear, but what would someone who sees the dead on a daily basis be afraid of? Things that should scare a child are almost an inconvenience to him. He chooses horror as an escape from actual horror in his life. It’s like the film is telling us that childhood is far scarier than actual phantasms.

In the opening scene, Norman is watching a B-horror zombie flick with his dead Grandma. And that’s not scary. But! Hold tight. The movie’s about to reveal something. Then, Norman’s father Perry enters the scene off-camera. We only see a long spiking shadow jab toward Norman, who sits on the floor. We understand that Perry is something Norman fears or at least resents. His father’s toxic masculinity is a running gag throughout the film – a piece of the dark comedy I’ll talk about in a minute – and we get the feeling that this is a source of anxiety for Norman. His hair stands straight up as if he’s perpetually terrified. It’s a cute detail and reminds us that this kid is resilient.

He is inactive in all of the scenes leading up to the zombies’ appearance. When stressed, he isolates himself, demanding to be left alone. It’s not until he is told that he must act that he becomes afraid of his horror-filled life. He’s afraid of asking for help, of leaning on someone else. He is given a lot of warnings about not closing himself off, including the appearance of Uncle Prenderghast, who shares Norman’s gift and closed himself off from the world. Norman could become exactly like him: living in a shack up on the hill, wearing a frayed vest, and a bag as one of his shoes.

Norman starts to feel more comfortable around others starting with Neil and eventually has to facedown the parts of himself that exist in the witch Aggie, his ancestor. His anger. The parts that drive other people away.

❤ NEIL. ❤

Oh, Maker, I love Neil so much. Neil deflates every situation and acts as our accidentally sarcastic Chorus. After witnessing Norman’s bullying for an entire school day, Neil spells it out for the viewer:

“You can’t stop bullying; it’s human nature. If you were bigger and dumber, you’d be a bully too. It’s called Survival of the Thickest.”

And he stands up for Norman, immediately. An immediate best friend. When his quarterback older brother Mitch (voiced by rapist Casey Affleck) tells Neil to stay away from “weirdos,” he responds, “Don’t blow this for me, Mitch. This one’s not weird. He talks to dead people!”

Neil serves as a kind of security blanket for Norman and the viewer. As long as Neil is in the same scene as Norman, Norman will be fine. Neil stands between an angry mob and Norman. He fights off the weird homeless guy shaking Norman’s coat by threatening to throw spicy hummus. He appears right when we need some warmth and cheer.

How young is too young when it comes to zombies?

Aside from Norman’s awesome bedroom and zombie slippers and alarm clocks, there are many horror references throughout. Did you catch any of these?:

- Norman sees Uncle Prenderghast watch him from a large hedge, just like Michael Myers in Halloween.

- Neil texts Norman, and his ringtone is the theme from Halloween. Then he sees Neil standing in a hockey mask outside the window. Yeah, it’s combining two things there, but who cares. (Sidebar: I have to say that when I saw this in theaters, this moment delighted me so much that I started scream-laughing like a lunatic, and everyone in the theater looked at me like I was a lunatic.)

- The zombie Judge drops his ear on the ground near Norman’s hiding place. Norman pushes the ear towards the zombie’s grasping hand so he won’t be found. This reminds me of a scene from Wrong Turn.

- I mean, I hope I don’t have to mention all of the Night of the Living Dead moments here. Right?

Although, for such a horror freak, Norman handles hiding from the zombies horribly. He enters a house where he knows there is a dead body. When he retreats to Prenderghast’s house with Alvin, he doesn’t take any time to find a weapon or secure the door. That is the hoarder’s nest of a mountain man with deep paranoia. You’re telling me he doesn’t have anything in there that’s weapon-like? Also, it’s clear from the start that Norman can understand the zombies. So from the very moment when they all claw out of the earth, he could have had a quick zombie chat and avoided the town mob. Come on, Norman. You’re better than that.

Pitch-black humor = black heart emoji

Although ParaNorman is very dark, it is also a very darkly hilarious movie. It approaches horrible things about Blithe Hollow and these characters with biting satire. It stings to watch because it’s so true:

- Blithe Hollow’s welcome sign is a smiling witch, who is being hanged, waving, with two waving Puritans. The caption says “A great place to hang!” Dear God.

- The school play is, at best, a story about killing a woman for having different beliefs. At worst, as we know, it is the story of the murder and disposal of a child’s body.

- The drama teacher! She wears a beret. She uses hard h’s (“The May-flow-herh!”). She is white-washing history with this play, and actually casts the only person of color to play the witch. This is normal for her, and she seems to be down with keeping it offensive, saying, “I won’t have this turn out like that wretched Kabuki debacle of ’09.”

- Outside of the play in the establishing shot, a child wails, “No! I don’t wanna go! I wanna go home!”

- Inside of the play, none of the family audience members are watching it with their eyes. They are a sea of cameras.

- Uncle Prenderghast’s spirit appears to Norman in the bathroom stall, saying he can’t pass on “until I pass on my duty” (pronounced “doo-dee,” as in poop).

- Perry says horrible things that I won’t repeat. His toxic ideas about manhood are the kind of funny that you can laugh at on film because these people and thoughts exist in our own reality, and it’s not funny when the flesh is in front of us.

- Alvin break-dancing. Just watch it again. It’s so perfect.

- A guy wants a snack. He: a. Goes into an alley to use a vending machine in the middle of the night. b. Stands in front of the machine screaming and refusing to flee from the zombies until the machine releases his chips. c. He saves the chips until the ending scene!

- Uncle Prenderghast’s house is hilariously bizarre. A few items I noted on this re-watching: a mannequin head, a chandelier made of forks, a book called You’re Not Creepy!

How to Critique the Government and American History: a puppet show

This was a theme that I could not shake the more the film rolled. We’ve talked about the critique or satire of specific people and places. Now I’m going to broaden that up and bring in Blithe Hollow as a town, the civilians as a mob, and America as a country and institution.

When you take away the zombie-varnish and laughs, this is a story about a little girl who was hunted down, put on trial, murdered, and who’s body was dumped in the woods. The worst part is that this happened to countless humans in this country throughout our history. It’s a horrible truth that hateful, murderous mobs are not that far off in our history. It is a rotten part of our nation’s fabric. A part we like to ignore. A part that isn’t told in history class. I’m glad that a kid’s movie has the ovaries to bring it up.

I do want to take a second here and mention that this is a very white movie. There are not many people of color, and I can’t tell if that was intentional or not. Salma is so smart an on-point with a supernatural and historic emergency that I feel like she could easily have defeated the zombies in an hour, tops. So was it intentional to use a white kid hero who runs away from his problems? I’m not sure.

The townsfolk become an angry mob in a flash. A lot of the physical comedy comes from these street brawl scenes until you realize that the zombies did the same thing in their lives, hunting down those who were different, beating them in the street. There’s a really smart and awful line at some point in the madness. Vending Machine Guy shouts, “Ain’t room for no more zombies in this town!” He says this in front of a fast food sign that advertises “meat and potatoes!” and “sugary drinks!” Let that sit with you for a second. Remind you of anything?

There’s a kind of mirror moment during the school play. Norman is crouched on the floor, with his schoolmates dressed as Puritan court members towering over him as the whole town shames him for his vision. Just like Aggie. Norman is still part of the cycle of cruelty, as was Aggie, and his uncle.

The breaking point in the narrative and the point of complete crisis for Norman happens at City Hall. There’s a beautiful shot of Norman collapsed on the floor, surrounded by papers and papers of the people who came before him. The floor resembles a compass, and he is completely lost. He is collapsed under the weight of the town’s horrific history, the malice of the townspeople. This is also his moment of realization, his rallying moment, and when his fear leaves him.

The final showdown between Aggie and Norman is pretty frightening and actually violent. The scene by Aggie’s tree and resting place still guts me after a millionth viewing. And it is also sweet and loving. And as was promised to us in our kid’s movie pact, Norman emerges from the forest a hero. Humanity hasn’t changed, the townspeople are all still ignorant monsters, but Norman took action and altered the town’s history forever.

That gives me hope, dear reader. See? Good things happen in horror sometimes. Until next time.